MAINE’S ROAD TO

GENDER

JUSTICE

Despite the critical gains of the last decades, gender inequality persists. In fact, some persistent gaps are actually widening. We spent the last several months listening to communities across Maine, gathering insight and ideas to move gender equality forward. This is how we get there.

Rigid gender norms and stereotypes are harmful to everyone, and create dangerous power dynamics and inequalities. Population level data in Maine shows gender inequalities in economic security, freedom from violence, health and wellness, representation in government systems, and civil rights and freedom from discrimination.

Gender-blind and gender-neutral policymaking create unintended gendered consequences in our laws. When policies are created assuming policies impact all genders the same way, it results in laws that have a disparate impact on particular sex or gender groups - even if it seems like the law has nothing to do with sex or gender.

A gender-responsive policy approach is when we approach policy making by considering and reducing the harmful effects of gender norms, roles and relations, including gender inequality.

A gender-responsive policy approach is when we approach policy making by considering and reducing the harmful effects of gender norms, roles and relations, including gender inequality.

Maine’s Road to Gender Justice is a chance to look at the key trends and forces affecting gender equity right now - and the policy solutions that will drive real change.

While we know that gender equity spans all aspects of the lives of women and people impacted by misogyny, this is a glimpse at some of the major forces driving inequity today, where we’ve come from, and how we can build on a road to a more gender-just future.

KEY ISSUES

Through our conversations with communities across Maine, we identified key issues that drive gender inequity. Here we provide a snapshot of why each issue is important, look at current data, and outline policy recommendations that will move us closer to gender equity. You may learn more about our methodology here.

“It’s not a lack of resources, (it’s) a lack of distribution.”

“If you don’t know it’s available, it’s not available.”

BIRTHING HEALTH

- LD 1113 Advisory Group interview participant on racial disparities in prenatal access to health

-

Health and mortality of pregnant and parenting people in the United States is among the worst in the developed world. As one of the only countries in the world without paid family leave and the only developed country without universal health care, birthing parents and infants are more likely to have poor pregnancy and postpartum health or die. The pandemic only made this worse - death rates among birthing parents skyrocketed during 2020 and 2021.

Pregnant people who are BIPOC are more likely to have different and negative experiences with care providers. BIPOC communities not only have worse birthing health outcomes in Maine than their white counterparts, they have less access to prenatal care, which is a key to overall health.

Ongoing medical care, mental health services, and addiction treatment are life-saving supports. Steep declines in mental health (especially among birthing parents), and increase in substance use, including during pregnancy, have serious health implications during and post-pregnancy. In 2022, the Mills Administration increased the amount of time MaineCare covers postpartum care from 60 days to 12 months. This covers care related to things such as recovery from childbirth, follow-ups on pregnancy complications, management of chronic health conditions, access to family planning, and mental health support.

Access to comprehensive sexuality education and access to contraception has resulted in a dramatic decline in teen pregnancy in Maine. Teen childbearing can carry health, economic, and social consequences for birthing parents and their children. Maine provides excellent access to contraception, and school-based health centers in some areas. While the number of sexually active teens has remained steady since 2002, are more likely to have different, which researchers cite as a primary driver to the decrease in teen pregnancy.

-

Birth Parent Health & Mortality Rates

The U.S. has the highest maternal mortality rate among developed nations. While causes for these deaths vary, 80% are preventable.

Maternal death rates skyrocketed during the first two years of the pandemic. COVID-19 contributed to 25% of deaths of pregnant people in 2020 and 2021. This included when the pandemic worsened factors contributing to maternal health disparities, like access to care. This was exacerbated for Black women, whose death rate at birth increased by 54% between 2019 and 2021. White women’s death rate at birth increased by 45%.

Maternal and infant death rates are significantly higher in states that ban or restrict abortion. Maternal deaths were 62% higher in states with abortion bans or significant restrictions. Infant death rates in the first week of life were 15% higher in abortion restrictive states.

Although 85.6% of pregnant people in Maine receive prenatal care during the first trimester—one of the highest rates in the nation—3.3% of pregnant people receive prenatal care late or not at all.

62.6% of Black people in Maine who are pregnant receive prenatal care compared to 82.5% of white pregnant people.

More than 40% of lower-income people in Maine received no health care in the year prior to their most recent pregnancy.

Infant Health & Mortality

After declining for six years (2013-2019), Maine’s infant mortality rate increased in 2020. In 2020 there were 72 deaths among Maine resident infants.

Between 2009-2017, the rate of infants in Maine exposed to addictive opiate drugs during pregnancy increased 165% and is more than four times the national average. In Maine, that is tied heavily to income. In 2018, the rate among those in the lowest income bracket was nearly 6 times higher than those in the highest income bracket. The rate was also 18 times higher among Medicaid recipients than among those with private insurance.

Pregnancy Rates & Maine Youth

Pregnancies among young Maine people aged 10-17 has fallen by 74% since 2008. However, disparities across all major race and ethnic groups persist. In 2018, the birth rate for Hispanic and Black teens ages 15-19 was almost double the rate among white teens and more than five times as high as the rate among Asians and Pacific Islanders.

“It is essential for healthcare providers in Maine to diversify their staff, their board, their leadership so healthcare seekers can see themselves in the systems that they’re accessing, and in the providers that they are getting care from.”

- Mareisa Weil, Maine Family Planning

-

Implement the recommendations of the LD 1113 Report by the Permanent Commission on the Status of Racial, Indigenous, and Tribal Populations. This 2022 report details numerous ways to decrease racial disparities and improve perinatal health outcomes in Maine, including:

Invest in relationship-centered care. Expanded access to doulas (nonmedical pregnancy support people), midwives, non-hospital births, and clinics with holistic, relationship-based care can all increase trusted, culturally specific support before, during, and after birth.

Improve structural access to prenatal care. This includes ensuring that all people in Maine have access to prenatal care regardless of their citizenship status; increasing the income limits on prenatal and postnatal MaineCare access; and increasing the number of providers - especially rural and culturally specific providers - focusing on birth.

Increase access to community-led education. Community-specific outreach, education, and support can increase health literacy, prenatal and postpartum connection to services, culturally-, regionally-, and age-specific resources on birthing and infant care.

Enhance statewide data collection, including community-led data gathering. Maine should continue system-wide data-focused efforts such as the Perinatal Systems of Care coalition, while expanding the opportunities for qualitative and participatory research and information gathering.

-

“Women in particular are vulnerable to exploitation or directive or condescending relationships or communication from physicians or other providers…. The more we can empower and educate around consent, the stronger we will be.”

- Pamela Corcoran, Belfast

“I feel like I'm always getting the message that I am not in control of my body.”

REPRODUCTIVE JUSTICE

- Maine undergraduate student

-

The ability to choose when and how to have a family is essential to racial, gender, and economic justice. It is essential to Maine communities. 59% of people who have an abortion already have at least one child. Abortion restrictions are about controlling the power of birthing parents, caregivers, and people who can become pregnant. Only you should decide whether you have a child - especially when you are the one bearing the costs associated with having one.

Abortion restrictions disproportionately hurt women of color. Structural racism and discrimination continue to contribute to significant income inequality among women of color, increasing their likelihood of not having adequate health insurance, utilizing Medicaid, or experiencing barriers such as limited transportation or lack of childcare. This is one way the Hyde Amendment, which bans federal funds for abortion care, forces a greater burden on women of color. Similar funding limits apply to Native Americans who receive care through the Indian Health Service.

Access to the full range of reproductive care, including abortion, is essential to economic security and justice. Women living in states with greater access to reproductive health care - such as insurance coverage for contraception and infertility treatments, Medicaid coverage of family-planning services, and state funding for medically necessary abortions - have higher incomes, are less likely to work part-time, are more likely to move from unemployment into employment, and face less occupational segregation than women in states with more limited reproductive health care options.

Increased access to the full range of reproductive care saves lives. Maine has instituted several ground-breaking policies which expand access to reproductive care. This includes:Comprehensive sexuality education, which increases use of contraceptives and decreases unwanted pregnancies.

Widespread access to emergency contraception.

Increased use of telehealth services.

Maine now requires all insurers that cover maternity care to also cover abortion care, ending the discriminatory practice of limiting abortion access for people on MaineCare. Maine now covers the cost of abortions barred from receiving federal reimbursement under the Hyde Amendment, which has exceptions only in cases of rape, incest, or when the patient’s life is threatened. Together, this expansion has limited the number of unwanted pregnancies, especially among teens, and helped to decrease barriers impacting different communities across Maine. Maine is one of only seven states that voluntarily has a policy that directs Medicaid to pay for all medically necessary abortions.

-

The need for reproductive health care is expensive, lifelong, and affects almost everyone. For example, in the United States:

There are more than 240,000 new cases of reproductive cancers each year.

99% of all sexually active women have used at least one contraceptive method.

1 in 4 women have had an abortion.

86% of women give birth at least once.

Half of all sexually active people will develop an STI before the age of 25.

1 in 10 people experience infertility.

Maternal and infant death rates are higher in states that ban or restrict abortion. Maternal deaths were 62% higher in states with abortion bans or significant restrictions. Infant death rates in the first week of life were 15% higher in abortion restrictive states.

There were 17 facilities providing abortions in Maine in 2020 and 16% of Maine women live in a county without a clinic providing abortion care.

Pregnancies among young people in Maine aged 10-17 has fallen by 74% since 2008. However, disparities across all major race and ethnic groups persist. In 2018, the birth rate for Hispanic and Black teens ages 15-19 was almost double the rate among white teens and more than five times as high as the rate among Asians and Pacific Islanders.

Americans’ confidence in the Supreme Court is at the lowest point it has been in 50 years of polling - due to Roe being overturned: 25% of Americans have confidence in the Supreme Court, down from 36% in 2021.

The ability to choose if, when, and how to have a family

is essential to racial, gender,

and economic justice.

-

Every person who wants one should have access to a safe, affordable abortion near their home. A federal law protecting the right to abortion in every state - such as the Women’s Health Protection Act - should be passed. With the fall of Roe vs. Wade, nation-wide protection through law is the only way forward.

At the federal level, overturn the discriminatory Hyde Amendment, which limits access to reproductive care, and disproportionately harms Black, brown, Indigenous, and low-income communities.

At the federal level, guarantee access to abortion care through public and private health insurance providers. Federal health insurance programs must cover abortion care, including Medicaid, Medicare and CHIP, Indian Health Services, the Federal Bureau of Prisons, and the Veterans Health Administration. block state or local governments from restricting coverage of abortion by private health insurance plans.

In Maine, continue to strengthen and expand our right to abortion. Expand the 1992 Reproductive Privacy Act by eliminating the ‘viability’ language, a vague and inconsistent nonmedical idea which requires many Mainers must travel out of state to access abortion care. Ensure that Maine will not cooperate with out of state investigations of abortion seekers or providers. Continue to expand access to telehealth-supported abortion care, which particularly supports rural Mainers. Consider constitutional protection for abortion as states such as Vermont have done. -

“Abortion is time-sensitive, essential care.”

- Mareisa Weil, Maine Family Planning

CHILD CARE

“Women lose their careers by not having child care.”

- Megan Marquis, teacher

-

Every Maine family deserves access to high quality, affordable, and culturally relevant child care. Every child care provider should be paid a wage that reflects the essential work they do. And it shouldn’t fall on parents or providers to foot the bill - or suffer without child care - for an inadequate system.

Affordable, flexible, family-focused child care is essential to participation in the workforce. It needs to work for all families at rates they can afford. And this women-led workforce is often underpaid. It's a vicious cycle - families can't afford child care, and child care workers aren't getting a living wage. A recent study found that mothers who were unable to find a child care program were significantly less likely to be employed than those with child care. There was no impact on fathers’ employment.

Our current unsustainable and discriminatory child care system is rooted in sexism and racism. Black women - as enslaved people and as domestic workers - have provided child care for white children. The 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act left out domestic workers - excluding many Black workers - from protections like the minimum wage and overtime eligibility. The lack of recognition and protections for child care workers persist today.

Expanding access to high-quality child care and paid family leave are critical for Maine families. Without these policies, families are forced to decrease their hours at work and their paycheck to care for their loved ones. Mothers are more likely to be pushed out of the workforce because, on average, they earn less than their husbands and are seen as more responsible for caregiving. The United States could add an estimated 5 million working people to our labor force with a national paid leave program combined with affordable child care.

-

Our nation loses $57 billion each year in economic productivity and revenue losses due to lack of access to child care.

86% of primary caregivers said problems with child care hurt their efforts or time commitment at work.

Since the start of the pandemic, over 5 million women and mothers have had to leave the workforce, devastating our economy and families.

Before the pandemic, mothers were 40 percent more likely than fathers to report that they had personally felt the negative impact of child care issues on their careers.

69.7% of Maine children under the age of 6 live in households where all parents work.

The average cost of daycare in 2021 for Maine families ranged from close to $5,500 a year for school-aged children to over $12,000 for infants. In comparison, an in-state student at the University of Maine paid $11,640 a year.

“If you need child care, you take whatever you can get, which is really sad.”

- Chrissie Davis, ME Assoc. of the

Education of Young Children

-

Continue to create child care programs that are affordable, high quality, and accessible to Maine families. Ensure that care is affordable by limiting overall costs to families to a certain percentage of income, expanding the state subsidy program, and increasing eligibility for Head Start to 200% of the Federal Poverty Level.

Expand tax assistance to help families meet the high costs of child care through refundable child care tax credits, which ensure that families across the income spectrum receive the benefit.

Establish a statewide system of paid family and medical leave. In particular, paid family and medical leave would alleviate the tremendous demand experienced in parts of the care workforce, especially infant child care.

Continue to improve child care subsidy rates and the subsidy system. The low payment rate, high level of paperwork, and unpredictable timing of payments from the state are all factors leading to some child care providers declining to accept the child care subsidy. Ensure that the subsidy reimbursement is based on enrollment, rather than attendance, to ensure financial stability for providers. Finally, streamline application and information sharing systems between the state and providers.

Close the wage gap between elementary school teachers and early childhood teachers through a wage supplement program, or tax credits for individuals who gain more credentials and stay in the early childhood classroom for a specific number of years. Continue to develop a statewide program for early childhood teachers that includes on-the-job professional training and continuous quality improvement.

Fund the online businesses, mobile apps, and household innovations developed to save people time and reduce household task burdens. -

“Just the impact of the lack of child care in cities and in rural areas where immigrants are finding permanent housing…. It is the isolation of women, staying home with children. They lack independence…. They lack child care options entirely.”

- Madeleine Saucier, Maine

Immigrants Rights

Coalition

“Just being a woman means your voice is easily censored…. People often say we're just overthinking when experiencing [workplace harassment].”

WORKPLACE EQUITY

- Migrant farm worker in Maine

“We don’t have a ton of straight, cisgender, white men who are Christian filing complaints about wages.”

-

Workplace equity is central to gender equity. Workplace challenges like harassment, discrimination, and wage disparities contribute to gender inequity across the lifespan, resulting in women’s lack of economic security as they age. Here is a snapshot of some of the challenges people of certain identities routinely face at work - and what can be done to address them.

Discrimination is underreported and at the intersection of different kinds of oppression. People and communities who are disenfranchised and historically excluded experience higher rates of discrimination. Those individuals may have fewer resources to report discrimination, fear not being believed, or face higher consequences for reporting, including losing employment and financial security. For example, sexual harassment in the workplace is underreported because workers fear facing retribution and retaliation. In fact, retaliation is the second-highest claim type at the Maine Human Rights Commission: workers have a reason to fear reporting the discrimination that they experience.

Discrimination in systems creates barriers to economic security and personal liberty. When people have multiple marginalized identities (for example, a Black trans woman) the likelihood that they must navigate these discriminatory barriers increases. Discrimination is disproportionately perpetrated against people who have less resources and work lower wage jobs, affecting women and people of color at higher rates.

Gender identity and race/ethnicity wage gaps persist. This is exacerbated by the fact that women, especially women of color, make up a disproportionate share of workers earning low wages and often work in undervalued, female-dominated occupations, such as home health aides or childcare workers. White men, especially married white men, continue to experience more economic security, both by having access to better wages and higher-quality jobs, as well as by being less affected by unemployment. The policies to address this will require a range of interlocking solutions, including wage transparency and paid family and medical leave.

Sexual harassment is still uniquely gendered, especially in certain industries. Though sexual harassment is a type of discrimination under the Maine Human Rights Act, in many industries it is still so pervasive that experiencing it feels like part of the job - especially for women and queer people. 71% of women restaurant workers have experienced sexual harassment - especially those working in tipped roles. Industries that rely on lower-wage, female-dominated workforces are more likely to have high rates of sexual harassment. -

While both men and women have dropped out of the workforce since the start of the pandemic, women’s workforce participation in 2021 was, on average, around 55 percent. This is the lowest it has been in 30 years.

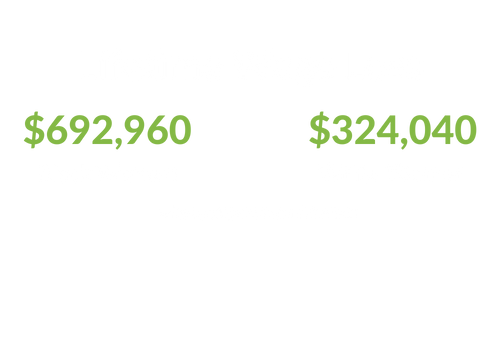

In Maine, the average wage gap between a woman’s income and a man’s is $0.83 (to the man’s $1.00), for a lifetime loss of $324,040. Black women in Maine are paid $0.66 for every dollar a white man makes, which amounts to a lifetime loss of more than $692,960. This means that she has to work until she’s 81 years old to be paid what a white man earns by the time he is 60 years old.

- Amy Sneirson, Maine

Human Rights Commission

-

Increase funding for the Maine Human Rights Commission. The Maine Human Rights Commission must have enough funding to address the number of complaints filed consistently and in a quality and timely manner. Increasing the responsiveness of this system will help address workplace inequity and encourage compliance with the Maine Human Rights Act. As noted in the FY 2022 Maine Human Rights Commission report, “Given all of this, the ongoing worldwide pandemic, and our extremely small staff, the volume of the Commission’s work in FY 2022 was overwhelming (and accomplished with very limited resources).”

Expand worker’s ability to address discrimination and harassment. Most notably, Maine must ban forced arbitration, which requires arbitration or mediation harassment or discrimination cases. It also prohibits workers from suing their employer. Workers can also address discrimination and harassment when employment standards that are transparent and uniform, such as in unionized workplaces.

Invest in education to increase system competency in the short-term, and to change discriminatory systems over time. This includes ensuring that the Maine Dept. of Education Learning Results aligns with the Maine Human Rights Act, especially related to education on bias and discrimination across housing, education, healthcare, and public benefits systems.

Reduce the gender identity and race/ethnicity wage gap.Increase wage transparency. Maine law already prohibits retaliation by employers against employees who share salary information with coworkers, but full transparency allows workers to compare salaries across different organizations, and across job titles and demographics within their own organization. Many states and countries already require public disclosure of salary ranges by position type.

Continue the ban on asking salary history in interviews, enacted into law in Maine in 2019.

Eliminate the tipped wage, which disproportionately affects women and tends to increase sexual harassment and other forms of discrimination.

Support labor unions. Gender and racial bias is minimized in environments where hiring, pay, and promotion criteria are more transparent, such as in businesses with labor unions. Women, especially women of color, who are affiliated with a union or whose job is covered by a collective bargaining agreement, earn higher wages and are much more likely to have employer-provided health insurance and retirement benefits than women who are not in unions or covered by union contracts. To support a women-centered economic agenda, voters, policymakers, and community leaders should:

Support policies that protect and strengthen collective bargaining and other basic worker protections.

Work with unions to help organize women and workers of color and encourage their development as leaders.

-

“(R)eporting will continue to show a substantial number of hostile environment complaints. Allegations based on sex continue in employment, housing, education…in many areas of women’s lives in Maine, from elementary school to systems serving older Mainers.”

- Amy Sneirson, Maine

Human Rights Commission

“We’ve seen girls go so far as getting themselves arrested. The helpers feel helpless, and if we have no resources then we feel helpless too.”

CARCERAL VIOLENCE

- Survivor Speak USA

interview participant

-

Women in Maine who are in the criminal justice system are overwhelmingly victims of previous trauma (especially sexual and domestic violence) and more likely to have committed nonviolent crimes that are likely related to that trauma. Expansion of early intervention services, such as children’s advocacy centers, sexual and domestic violence services, mental health services, and substance use treatment, is a more holistic and better use of public resources than incarceration.

Criminalization of non-violent activities increases violence for all. For example, criminalizing consensual sex work increases violence against sex workers by clients, police, and the public. It also limits sex workers’ access to health care systems and justice, and increases their economic instability. Sex workers are more likely to be communities who are already marginalized by mainstream systems, such as trans women of color. Criminalization simply compounds that experience.

The criminal justice system itself perpetuates violence. Women experience violence while incarcerated, and incarceration and subsequent criminal records increase the barriers to employment, housing, safety net services, and education. Incarceration also disrupts family connections, inflicting trauma on another generation.

The criminal justice system is falsely seen as a means of accountability for gender-based violence. The data is clear that this is often not victim-centered, and many victims and survivors report desiring more holistic forms of accountability. -

The number of women in Maine’s jails increased 64 times between 1970 (4 women) and 2015 (258 women), while the number of women in Maine’s prisons has increased more than 15 times from 10 in 1978 to 152 in 2017. Women now make up almost 1 in 4 jail admissions, up from fewer than 1 in 10 in 1983. At the same time, men’s jail admissions have declined by 26% since 2008.

Maine’s Department of Corrections reports that 72% of women in its prisons in 2018 were there on drug and theft charges.

The annual cost per inmate in 2017 was $43,773.

Overall, Maine leads our regional peers in incarceration. Maine has an incarceration rate of 363 per 100,000 people (including prisons, jails, immigration detention, and juvenile justice facilities), meaning that it has a higher percentage of incarcerated people than many wealthy democracies.

Incarcerated women are 30 times more likely to have experienced rape than women outside of prison.

The research is clear: criminalizing sex work, including buying but not selling sex (known as the “end-demand” model), increases the risk of violence and threatens the safety of sex workers.

“We wrote a bill when it comes to incarcerated trans rights. But that hasn’t stopped institutions putting trans people in solitary confinement.”

- Maya Williams,

MaineTransNet

-

Decrease criminalization of nonviolent activities. This includes:

Reducing classes of drug related crimes.

Reducing criminalization of other nonviolent crimes, such as sex work.

Reducing the impact of criminal records on future opportunities, by allowing records to become confidential, or allowing people with certain criminal records to access housing and employment opportunities (such as ‘ban the box’ legislation, which was passed by the Legislature but vetoed in 2018).

Increase investment in programming that prevents and responds to trauma.

Ensure that programming in carceral settings is gender-responsive and supports connections with families and communities. The Maine Department of Corrections should ensure that incarcerated parents and caregivers have visitation with minor children that prioritizes the mental and emotional well-being of the children; and should address the specific health care needs of women housed in Maine’s correctional facilities.

Gender-responsive incarceration practices must extend to trans inmates in policy and practice. Maine law should ensure that incarcerated people are housed according to their gender identity, aligning with the federal Prison Rape Elimination Act. Trans-specific health care should be required in Maine carceral settings.

-

“When I was being pimped out, not just once, but three times I caught prostitution charges, and each time it tore me apart. What it was like to stand before a judge…. What that does to a person inside.”

- Survivor Speak USA interview

participant

“…Only a very small minority of survivors will report to law enforcement and engage with the criminal justice systems. For those who do, the outcomes rarely reflect their hopes and expectations. As a result, survivors often face an all-or-nothing response.”

PERVASIVE VIOLENCE

- Elizabeth Ward Saxl,

Maine Coalition Against

Sexual Assault

-

Sexual violence, intimate partner violence, and stalking are public health crises in Maine, disproportionately affecting women and children. 40% women in Maine have experienced sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by a partner at some point in their lifetime—nearly as many as every person in Maine living north of Augusta.

This violence results in significant disparities across every aspect of physical, emotional, and financial well-being. These costs—tangible and intangible—are shouldered by people, families, communities, and the state. Most state systems, from mental health to criminal justice to social services, share the burden of this violence.

Links between experiencing violence, economic security, and the ability to access services and support systems are clear. Low-income Mainers and those without regular access to food and housing stability are more likely to experience domestic violence. Once they do, they face greater barriers in accessing services. According to MCEDV, 98% of domestic violence resource center providers have worked with a survivor who didn’t have reliable access to transportation. According to MCEDV’s report on economic abuse, “abuse creates economic instability. And, in turn, economic instability reduces safety options for survivors and makes them more vulnerable to continued violence and isolation. The ability to access safety often hinges on access to economic resources, and while abuse can occur in any income bracket, people in poverty are nearly twice as likely to experience domestic violence.” Staff at Maine Coalition Against Sexual Assault (MECASA) reiterate this point: “Survivors’ access to transportation is a majorly overlooked factor in whether they can access healthcare, services, resources, or even engage in the legal system.”

There are dramatic disparities in the experience of violence across different populations, especially sexual violence. The Maine Integrated Youth Health Survey, conducted every other year by the Maine Centers for Disease Control, is perhaps Maine’s best resource for Maine-specific data broken out by gender, race, and sexual orientation. The data on high school students is especially revealing: 7.5% of all high school students report experiencing forced sexual intercourse; for girls, that number rises to nearly 11%. For American Indian/Native Alaskan girls, it rises to over 21%; for trans boys, it is a full 31%. Looking at the data in the aggregate hides the real impact of violence on specific communities.We also know that the data is not usually available to show the true extent of violence in historically excluded communities. In the words of Heather Zimmerman of Preble Street, “The amount of sexual violence that exists for women in homelessness is unfathomable and probably uncapturable.” This is true for any population that is not readily visible to mainstream systems, not only unhoused Mainers, but those who are incarcerated, who live in residential facilities, who are experiencing sexual exploitation, and more. Increasingly, there are programs specifically for and by affected communities, but as Lisa Sockabasin of Wabanaki Public Health notes, “Our system is not set up to support those organizations that are most effective to do the work.”

The criminal justice system is an inadequate route to justice for many survivors. Many survivors of intimate partner and sexual violence do not choose to report to law enforcement. In many cases law enforcement is not able to effectively respond to these crimes. For example, approximately 400 sexual assaults are reported to Maine law enforcement in any given year - out of approximately 14,000. Of these, very few cases result in prosecution.Elizabeth Ward Saxl of the Maine Coalition Against Sexual Assault, notes: “One of the priorities we have committed ourselves to is increasing access to alternative paths to justice and healing for survivors. This was an explicit acknowledgement that only a very small minority of survivors will make a report to law enforcement and engage with the criminal justice systems. And for those who do, the final outcomes rarely reflect their hopes and expectations. As a result, survivors often face an all-or-nothing response. We are committed to supporting victim-centered efforts to explore alternative paths like restorative justice as well as approaches like deferred disposition.”

Alternative paths to justice are especially supportive of victims and survivors from oppressed communities. For example, Black or trans survivors may be less likely to report crimes they experience to the criminal justice system, as they have been disproportionately harmed by this system.

-

In Maine, 40% of women aged 18 and older report having experienced sexual violence, physical violence, and/or stalking by a partner at some point in their lifetime.

Nearly one-quarter of Mainers have experienced rape or attempted rape in their lifetime, women at more than three times the rate of men (35.7% vs 10.1%).

In 2019, 12,516 survivors in Maine reached out for support from Maine's domestic violence resource centers, representing more than 1% of Maine's entire population.

Nearly 1 in 7 Maine women has been the victim of stalking behavior. Unpartnered female respondents (single, divorced, or widowed) reported being the recipients of unwanted stalking behaviors more than twice as often as women who were married or in a relationship (23.9% vs 9.3%).

Individual rape victims experience an estimated lifetime economic cost of $122,461. This translates to slightly more than three full years’ of earnings for women working full-time, year-round in Maine.

Food and housing insecurity are strongly correlated with experiencing intimate partner and sexual violence, even when controlling for age, family income, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status.

In a recent survey of Mainers experiencing intimate partner violence, 62% reported that their abusive partners made it difficult for them to continue working at their current place of employment, and nearly all of the respondents reported that the abuse they experienced affected their ability to meet their daily needs (food, shelter, clothing). 8 in 10 reported that the economic abuse committed by their partners while in the relationship made it difficult to separate from their abusive partners.

“We had to survive the streets. We’ve had to survive domestic violence at the age of 6 and addiction.”

- Maine survivor of violence

-

Support policies aimed at enhancing survivors’ economic stability, including increased workplace protections, affordable child care, and ease of access to public benefits and safety net programs.

Increase access to alternative forms of justice. This includes supporting policies and resources to expand restorative justice programming. For example, a pilot partnership between the Restorative Justice Institute of Maine and MECASA is demonstrating some success in offering less criminalization and more community connection and accountability in some circumstances.

Create and fund a statewide infrastructure to support Title IX coordination and implementation. Title IX requires addressing sexual harassment and assault as gender-based discrimination within educational settings; mandatory coordinators are often tasked with implementing complex federal law with limited information or resources.

Increase state funding for Maine’s sexual and domestic violence service providers, including community-led organizations. The services are still deeply under-resourced, and the workforce is deeply underpaid. Additional resources can support providers to overcome barriers such as access to transportation or to establish new and innovative programming, such as video conferencing or helpline text and chat options for survivors, and can increase access to healing services and relieve regional disparities.

Support community-specific and community-led organizations and solutions. Community-led organizations can provide accessible, appropriate, and high-quality services to survivors who are disproportionately affected by sexual and domestic violence. Examples of the ways that community-led organizations are offering community-specific, culturally appropriate services include the Immigrant Resource Center of Maine, the member providers of the Wabanaki Women’s Coalition, Her Safety Net, an immigrant-led domestic violence support in Lewiston, and the sexual and domestic violence program hosted by Maine TransNet. -

“I was sexually assaulted by my mother’s boyfriend, but my mother never believed me. Why would I lie about something like that? So I went from foster home to foster home, and let me tell you, it didn’t get any better.”

- Maine survivor of

sexual violence

CARE WORK & LABOR

“(Women) are expected to uplift their entire community for free just because it is their community.”

- Madeleine Saucier, Maine

Immigrants Rights Coalition

-

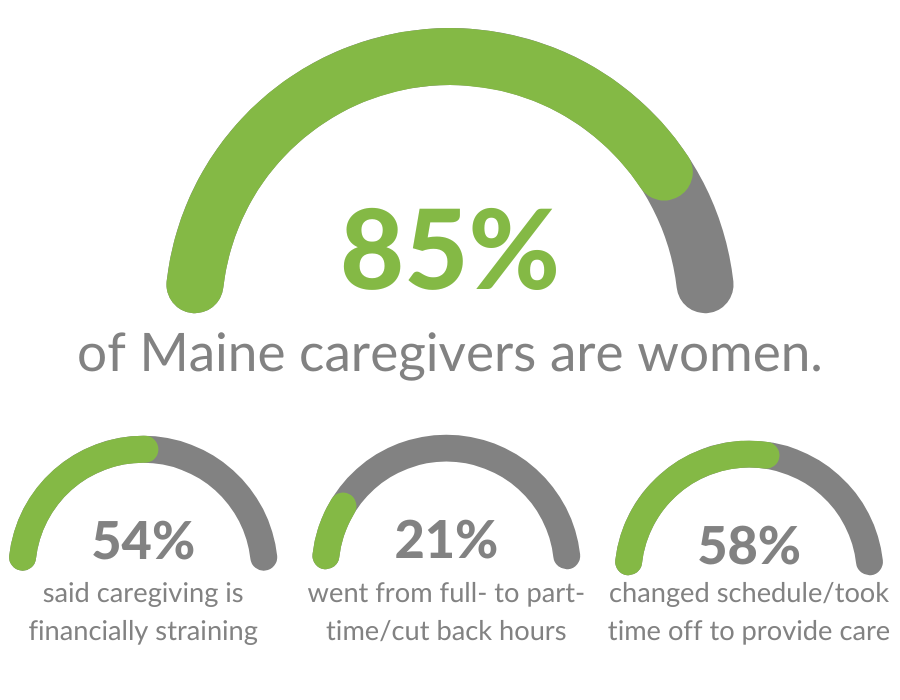

Care work is the invisible and undervalued underpinning of our economy. Care work - the paid or unpaid work of looking after the physical, emotional, and developmental needs of others - is also highly gendered - 85% of Maine caregivers are women.

Unpaid family care work seems “free,” so it gets left out of most policy conversations. But care work comes at a cost, including caregivers’ and parents’ ability to fully participate in the workplace, save for retirement, find time to give back to our communities, and do what they need to for their families. This unpaid care labor means women are more likely to work part-time or to leave the workforce, limiting their ability to access health insurance or save for retirement, and reducing Social Security benefits in later life.

Professional caregivers - regardless if they care for children, older adults, or differently abled people—are also underpaid and undervalued. Most of these workers are women and, nationally, they are more likely to be women of color. These roles are uniquely undervalued in part because they are traditionally ‘women’s roles.’ Research shows that when women join industries that pay more, wages go down as employers value the work less.

Taken together, wage disparities in female-dominated industries (and across the board), undervalued labor, and unpaid care labor mean that women enter their older years far less financially secure than men. Thousands of older Maine women can't meet their basic needs.

The lack of a care infrastructure doesn’t only harm caregivers themselves. In part because the childcare and direct care workforces are so undervalued, they are facing critical workforce shortages, which exacerbates demand and decreases affordability for all families. Additionally, the lack of care infrastructure requires families to continue to rely on unpaid and informal care, which depresses women’s workforce participation and the economy as a whole.

-

85% of Maine’s caregivers are women.

86 percent of primary caregivers - mostly women - said problems with child care hurt their efforts or time commitment at work.

Before the pandemic, mothers were 40 percent more likely than fathers to report that they had personally felt the negative impact of child care issues on their careers.States with Paid Family and Medical Leave programs see a 50% reduction in the number of women leaving their job within five years of welcoming a child.

Maine caregivers contribute an unpaid $2 billion to Maine’s economy each year.

The average 50+ Maine adult who leaves the workforce to care for an aging parent loses out on over $300K in wages.

Women 80+ are 2x more likely to live in poverty than men 80+ - in large part as a result of the ‘care penalty’ they pay over the lifetime

“How do we get people into jobs if we don’t pay them?”

- Laurie, Orono

-

Implement a system of Paid Family and Medical Leave for Maine. A comprehensive paid leave program means every family in Maine has the time they need to welcome a new baby, care for themselves, tend to a loved one, support themselves during a loved one’s military deployment, or recover from domestic abuse. Without such a system, it is primarily women taking time away from work to provide this essential care, disrupting their current and future economic security.

Ensure that caregiving professions, such as childcare providers and the direct care workforce, receive livable wages, paid time off, high quality training, and a meaningful ladder for career advancement. Several key advances have been made in recent years - such as increases in wages for direct care workers - but more must be done, and it is the role of the state to ensure that these essential services are well compensated and still remain affordable to the people they serve.

Ensure that caregiving responsibilities are acknowledged and compensated —and that caregivers who take time out of the paid workforce to provide care are not penalized—by:

Protecting working people from employment discrimination, including through policies to ensure that pregnant people and caregivers are not forced to choose between meeting their responsibilities at work and caring for their families.

Ensuring that part-time workers—who are disproportionately women, and often work part time to accommodate caregiving responsibilities— receive pay, benefits, and promotion opportunities that are equal to those offered to full-time employees in comparable positions.

Addressing the economic costs to women that result from time spent out of the workforce caring for children or other family members, through policies such as Social Security caregiver credits. Continue to strengthen and expand Maine’s caregiver grant program.

At the federal level, protect and expand Social Security and Medicare; add a caregiving credit to Social Security benefits to cover reduced time in the labor force due to caring for family. Increase benefits to ensure adequacy and improve cost of living adjustments.

Implement a Universal Basic Income, so that families are not obligated to find paid care in order to make ends meet. Parents who would like to care for their children, aging parents, and loved ones with disabilities should be able to afford to.

-

Providing Unpaid Household and Care Work in the United States: Uncovering Inequality

Women’s Unpaid Labor is Worth $10,900,000,000,000

Other countries have a social safety net. The U.S. has women.

Why Unpaid Labor Is More Likely to Hurt Women’s Mental Health Than Men’s

The Economic Security of Older Women in Maine: A Data Report

Caregivers are in high demand, in short supply, and underpaid (when they are paid at all). They're also mostly women.

“Maine women who live alone, basically at least half of them, don’t have enough money to meet their basic needs.”

- Jess Maurer, Maine

Council on Aging

SYSTEMS & REPRESENTATION

“The system was never built to include everyone.”

- LD 1113 Advisory Group

interview participant

-

Throughout every policy conversation, there are underlying questions about whether and how our structures contribute to - or prevent - equity. Many of our government structures, from voting to budgets to leadership, were built originally for and by white, land-owning men. The imprint of those decisions still exists today, and part of our work for anti-racist, feminist futures means unraveling that imprint and building more accessible, equitable structures.

When we think of ‘systems and representation’ we must ask ourselves how we build government structures that recognize and respond to gender, race, and class inequality. Who has unfettered access to voting, and who waits longer in lines? Who is more represented and therefore making decisions in every level of government power, from city councils to the U.S. President? Do budgets and tax structures indirectly help or harm some classes of people? Are government systems and accountability effectively tracking, analyzing, responding to, and being held accountable in their roles?We must continue to work for the promise of a representative democracy. Voting should be easy and accessible for all people. We should ensure that all Mainers have access to the ballot, regardless of mobility, caretaking responsibilities, job duties, transportation, and other concerns. People should see themselves and their experiences reflected in leadership and those who are making decisions.

Data and information should center both quantitative information and lived experiences. It must be collected, analyzed, and presented in accessible ways that highlight structural inequities.

Government structures and branches should be fair, just, and representative. They must be adequately staffed and funded to respond to and be accountable to community needs.

State budgets should raise and spend money in ways that repair past inequalities and build a more equitable future for all.

-

Women make up 44.1% of the Maine legislature, which is significantly higher than the national total of 32.7%.

Women make up 29% of Maine’s judiciary - women are 25 of 85 judges in Maine.

Legislative salary in Maine: $16,245.12 in year one / $11,668.32 in year two

Number of years that the Maine Permanent Commission on the Status of Women has had staffing: Zero

“The more that we look at existing data sets, the more we make the people with lived experience invisible. Those datasets were designed to exclude the people who are most left out of the process and will be the ones not served by the existing data.”

- Lisa Sockabasin, Co-CEO,

Wabanaki Public Health &

Wellness

-

Create statewide structures that acknowledge, disrupt, and dismantle gender inequity. This includes:

Ensure that the Maine Constitution fully protects all Mainers regardless of sex, sexual orientation, or gender identity.

Fully fund Maine’s Permanent Commission on the Status of Women. Though staff in the Secretary of State’s Office have worked hard to support the Commission, there has never been dedicated staffing or resources to ensure that the Commission is able to meet its mission of regular reporting on the status of women in Maine. As a result, reports are largely collected through uncompensated volunteer resources, and the state does not have a reliable central source for this critical function.

Create staffing structures such as gender-specific roles inside key state agencies. For example, Maine’s Centers for Disease Control held a Women’s Health Coordinator role for many years, until the position was eliminated in the early 2010s. This role offered pivotal support such as compiling the biennial Maine Women’s Health Report.

Fully fund structures like the Maine Human Rights Commission that conduct essential civil rights accountability. Under-funding these critical entities means that the state does not meet the obligations of the civil right act. Many of these gaps disproportionately affect women and people from other protected classes.

Invest in more meaningful data systems that expand the value and availability of public health data, as well as the informing power of stories and lived experience.

Invest in central data collection and analysis that regularly presents disaggregated data on gender,race, ethnicity, and age. The state has access to many public health data sets such as the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System and the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System. However, resources are rarely available to analyze that information and regularly accessibly present trends and findings to the public.

Invest in qualitative data, storytelling, and the sharing of lived experiences as an essential means of data collection. Support the development of initiatives that honor the ability of communities to gather their own data and ensure the health and sovereignty of that data.

Invest in efforts that allow productive and mutually beneficial data sharing between mainstream public health systems and community-led data initiatives.

Support efforts that ensure the full participation of historically excluded populations - including women - in democratic structures.

Ensure accessible voting which respects the needs of caregivers; people with several jobs or jobs outside the ‘9-5’ town hall hours; and those with limited transportation or mobility. This includes ensuring that polling places are reasonably close to people's homes.

Continue to expand systems which allow more people and people of diverse lived experiences to run for and hold office. This includes continuing Maine’s ‘Clean Elections’ program, increasing legislative salaries to ensure that people of all income levels can afford to run for and hold office; and identifying innovative solutions to do the same, such as childcare or caregiver stipends.

Maine’s Judiciary is the least representative branch of government, and relies on a system of self-nomination (a method that excludes women). It is time for an analysis of the gender and race disparity in Maine’s judiciary and the factors that drive it, in order to identify meaningful solutions.

State policy makers must pass budgets that invest funding in a way that recognizes and alleviates gender inequity.

Raise the income tax brackets to generate more revenue from Mainers who can afford to contribute more. The income tax is one of the most equitable ways to raise revenues to ensure a healthy, supported Maine. By accounting for ability to pay – unlike sales and property taxes – the income tax has a less harmful effect on lower income Mainers (who are more often women). In the last administration, significant roll-backs of income tax reduced the total income that Maine generates, as well as the equity of the structure.

Build budgets that actually invest in and meet the basic needs of its people, including building more equitable systems in the ways we’ve noted. When a budget does not meet the basic needs of its people, women – especially Black, brown, and Indigenous women, women with disabilities, and other women with marginalized identities – are the ones most likely to be left without access to adequate health care, food, and overall economic security.

-

Gender Equality Through Public Policy: Creating Gender-Responsive Policy in Maine

A Guide to Gender Responsive Budgeting

The State of Women’s Leadership - And How to Continue Changing the Face of US Politics

The State of Maine Democracy

Women in State Legislatures 2023

The Gavel Gap toolkit from American Constitution Society

“The Commission’s funding and lack or resources is a substantial barrier to people trying to get access to justice.”

- Amy Sneirson, Director

of Maine Human Rights

Commission

Information gathered for this project included four primary efforts:

A review of population-level data sources, from the United States Census to the Maine Integrated Youth Health Survey. Where we were able to, we connected directly with individuals who oversee or contribute to those data sources. We’d like to acknowledge the support of staff from Maine Kids Count, Maine Integrated Youth Health Survey, Maine Center for Economic Policy, the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention Adolescent Health Program, and Wabanaki Public Health.

We hosted ten community listening sessions, some in person, virtually, and hybrid. We’d like to thank community partners who co-hosted sessions with their membership, including the Maine Council on Aging, Survivor Speak USA, Mano en Mano, Hardy Girls Healthy Women, and the Maine Association for the Education of Young Children.

METHODOLOGY

Discussion and outreach with community partners to learn about their observations. This feedback was collected through surveys or 30-60-minute interviews with partners. We’d like to acknowledge and thank Jess Bedard of the Maine Coalition Against Sexual Assault; Amy Sneirson of the Maine Human Rights Commission; Helen Hemminger of Maine Children’s Alliance; Maya Williams, Quinn Gormley, and Rook Hine of Maine TransNet; Mark Mclnerney of the Department of Labor; James Myall of the Maine center for Economic Policy; Mareisa Weil of Maine Family Planning; Jean Zimmerman with the Maine Integrated youth Health Survey; and Andrea Mancuso of Maine Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

A literature review of a range of policy resources, both local and national, such as materials from the Institute on Women and Policy Research. We’d like to acknowledge and thank staff from Family Values at Work and the Institute on Women and Policy Research their support.

Much of this work was supported by the 2022 Linda Smith Dyer Fellow, Mariah Wood, University of Maine School of Law 2023. Thank you, Mariah!